Empirics of financial contagion

Recently, I attended the SYRTO conferences in Amsterdam, which contained two days worth of presentations on financial contagion and systemic risk. The conference demonstrated how much progress has been made on these topics but also highlighted the challenges that the empirical literature on financial contagion still faces.

Financial contagion

Contagion, the spread of a financial crisis from one country or market to another, is a causal concept. This implies a number of econometric challenges that I discussed in a paper with Hashem Pesaran in 2007. Many papers in this literature start with the statement that no unique (empirical) definition of financial contagion exists. Yet, this ignores the fact that politicians have a clear definition in mind when they talk about financial contagion: a crisis in one country, e.g. Ireland, causes a crisis in another, e.g. Italy.

The question of causality is important for economic policy. If there is a causal effect from a sovereign debt crisis in Ireland to a sovereign debt crisis in Italy, then a bail-out of Ireland could stop the domino effect. If Ireland and Italy were affected by a common factor, then a bail-out of one country will have no effect on the second country. During the European sovereign debt crisis, politicians justified bail-outs with arguments of financial contagion (e.g. Josef Pröll’s quote reported in the Irish Times). Yet, as far as I am aware, there is no firm evidence in the literature for or against the existence of contagion. And this may not come as a surprise, given that establishing causality in financial data is generally no easy task.

Pearson’s rho vs. Kendall’s tau

A short post-script to my discussion of the paper by Arakelian et al. at the SYRTO conference. The paper uses Kendall’s tau to measure contagion because it assumes non-elliptic distributions. While this ignores the issue of causality described above, it might address the shortcoming of Pearson’s rho, which has been discussed by Forbes and Rigobon in their 2002 JF paper. In short, Forbes and Rigobon show that changes in correlations can be just as much caused by increases in volatility as by contagion.

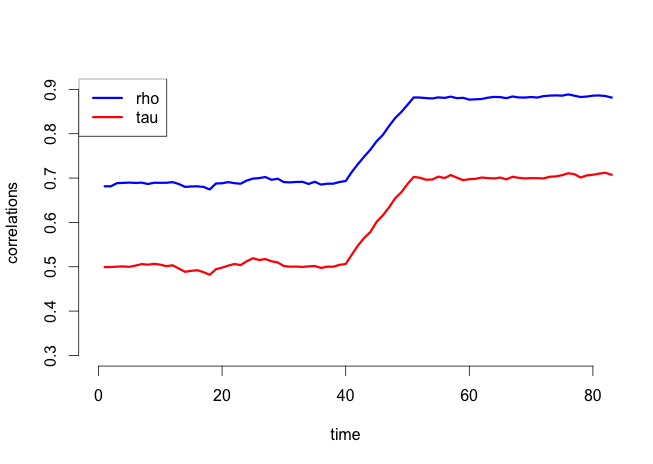

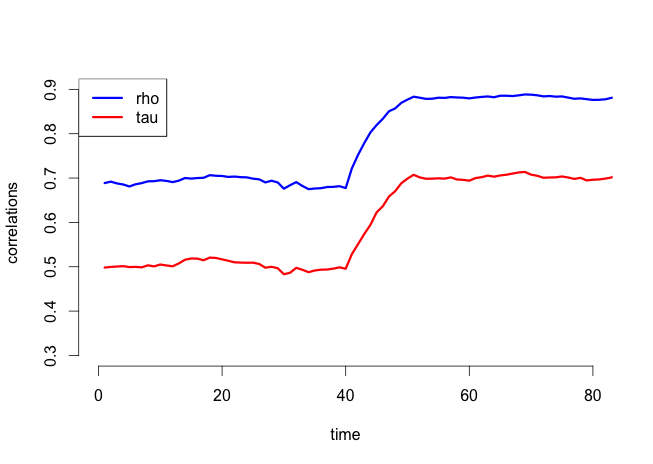

Unfortunately, the same is true for Kendall’s tau. In a miniature Monte Carlo experiment, I generated data from a linear model with normally distributed errors: first with a change in the regression coefficient, which represents financial contagion, and, second, with a change in the volatility. The plots below contain estimates of Pearson’s rho and Kendall’s tau from rolling windows. In the first plot, the coefficient linking one variable (think financial market) to the other changes at period 40, which you can think of as contagion. In the second plot, the coefficient remains the same so that there is no contagion but the volatility changes. As expected, Pearson’s rho looks essentially identical in the two plots, so it cannot distinguish between the two — but neither can Kendall’s tau.

Financial networks

Another approach with a slightly different aim may offer some hope. This approach analyses the network that financial institutions span. These papers, including that presented by Marco van der Leij at the SYRTO conference, do not attempt to establish contagion in the sense outlined above. Rather they investigate the relevance of individual institutions within the financial network. If such an analysis could be extended to multiple countries then we might be able to address the question of contagion.